Listening In: New Research Aims to Decode the Gobbles of Wild Turkeys

Every spring, the unmistakable gobble of a wild turkey signals the arrival of turkey season. But for wildlife researchers, that sound may soon do more than just alert hunters — it could unlock answers to pressing questions in wild turkey management.

A groundbreaking study led by Patrick Wightman, Ph. D, at the University of Georgia is innovating wild turkey research by placing miniaturized audio recorders directly on male turkeys to understand their gobbling behavior at the individual level.

This project aims to explore two key goals: determine how hunting affects gobbling activity and assess whether turkey calls can be used to more accurately estimate how many males are on the landscape.

Since 2014, Wightman and his collaborators at the University of Georgia and Louisiana State University have been deploying audio recording units (ARUs) across the Southeast to monitor gobbling activity. These devices have helped researchers establish that hunting pressure reduces gobbling behavior. But the real mystery lies in why.

“There are three main possibilities,” Wightman explained. “Turkeys may be removed through harvest, they may move away from recording areas, or they may stay put but gobble less. All three are occurring, but we can’t determine the relative contribution of each using landscape-level data alone.”

That’s where this new study comes in. By placing recorders and GPS transmitters directly on birds, researchers can confirm whether an individual is alive, determine its location, and asses whether it's gobbling or not.

These backpack-style devices are tiny, high-tech microphones designed to record about 70 minutes of audio each morning — centered around sunrise, the peak time for gobbling. The project deployed 30 recorders this past season across two study sites: an un-hunted area at South Carolina’s Savannah River Site and hunted areas in Georgia’s Piedmont region.

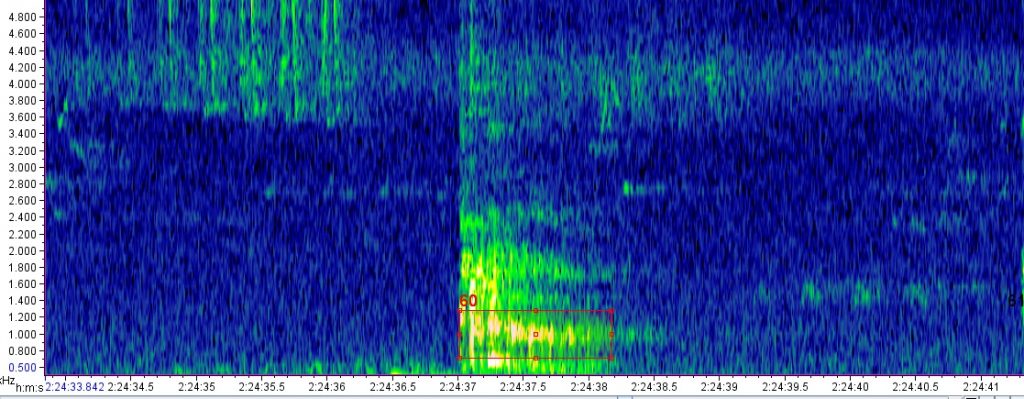

It wasn’t without hurdles. Sensitivity settings on the microphones led to distorted audio — so sensitive, in fact, that researchers could hear the birds’ heartbeats clearly but not their gobbles.

“It was so sensitive, it clipped loud noises,” Wightman said. “We could hear things like car horns and crows off in the distance, and feathers ruffling as the bird moved, it was so sensitive you could hear their heartbeat. Which is very interesting, but unfortunately, the gobble itself was too loud to be captured clearly. When you listen back to the audio, there is an event that occurs that is so loud that it’s not audible. It lasts about 3 seconds, the length of a gobble, and sometimes you can catch the faint end of a gobble, but it’s not clear.”

Despite the setback, the research team has been able to cross-reference clipped audio from the backpack recorders with nearby ARU recordings to confirm that some of these events were indeed gobbles. Adjustments to sensitivity settings and upcoming trials with captive turkeys are expected to improve the recordings for the 2026 field season.

Perhaps the most exciting potential outcome of this project is its ability to help estimate male turkey abundance, a notoriously tricky metric. If researchers can confirm how often an individual gobbles — and if they can distinguish between birds by their unique vocalizations — they could revolutionize how states monitor turkey populations.

“We hope to train machine learning models to recognize individual gobbles, much like voice recognition,” Wightman said. “If that works, we could go back through over a decade of ARU data and identify individual birds, giving us new insights into population dynamics. At the very least, we’ll gain a better understanding of individual gobbling propensity and detection probability, which will significantly improve models that estimate abundance based on calling rates.”

The implications are enormous. Wildlife managers could use gobble data to estimate how many males are in a given area and then set harvest quotas accordingly. This would allow for more responsive, science-based hunting regulations that adapt to annual changes in turkey numbers.

Though this first season yielded mixed results, Wightman is optimistic. The team plans to redeploy updated recorders in early 2026, aiming for cleaner audio and a larger sample size. The long-term goal is to make this technique scalable, providing an efficient and accurate tool for states across the country.

“There’s always risk involved when deploying new technology,” Wightman admits. “But the potential insights are worth it. This new technology gives us a chance to collect data we never have before.”

The NWTF invested funds into the above project along with eight other wild turkey research projects across the United States, totaling $655,447 for the organization's 2024 RFP allocation.

Since 2022, with partner funds leveraged at more than a 10-to-1 ratio, the NWTF, its chapters, members and partners have combined to put more than $18 million toward wild turkey research. This number will increase as the NWTF's national Science and Planning team is slated to fund more wild turkey research projects later this year.

Thanks to support from dedicated partners — such as the Bass Pro Shops and Cabela’s Outdoor Fund, Mossy Oak and NWTF state chapters — the RFP program is an aggressive, annual effort to fund critical wild turkey research projects nationwide.