Merriam’s in Texas? Why the Answer Matters

Texas has long been considered one of the premier destinations for turkey hunters. Its vast and diverse landscapes hold strong, huntable populations of Rio Grande wild turkeys, drawing hunters from across the country. Yet in the far western reaches of the state lies an unanswered question that has persisted for years: do Merriam’s wild turkeys truly remain in Texas, or have they blended into hybrid lineages that no longer resemble the pure birds hunters expect to find? Additionally, by combining genetic analysis with regional survey data and existing research on survival and reproduction, scientists are working to clarify the trajectory of these turkey populations.

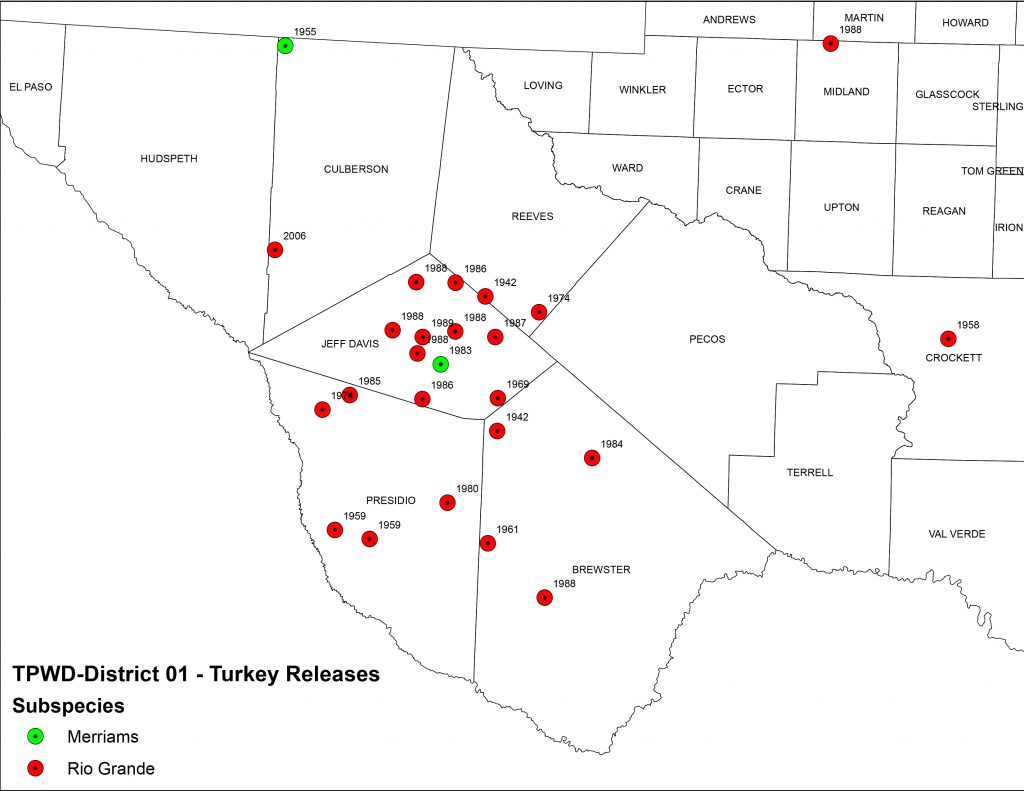

“Texas Parks and Wildlife Department restocked Merriam’s Wild Turkeys in the Guadalupe Mountains in 1955 and in the Davis Mountains in 1983 from New Mexico and they held on for decades,” said Jason Hardin, wild turkey program coordinator for Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. “However, Rio Grande wild turkeys, restocked nearby by TPWD, moved into the landscape and hybridization has been documented.”

This research will give biologists a clearer understanding of the true genetic makeup of wild turkeys in the Trans-Pecos region, while also helping hunters better understand what they may actually be harvesting in this part of the state.

Historical distribution maps have long suggested their presence in the Trans-Pecos region, but when you talk to hunters and biologists who spend their days on the ground, the answer becomes far less certain. Many say they rarely encounter birds with the bright white tail feathers of a classic Merriam’s, while others insist they see them, though perhaps not in the numbers Texas once claimed. After decades of turkey management, translocations and natural range shifts, nobody can say with confidence what subspecies is actually out there.

“You talk to some folks in New Mexico, and they’ll tell you Texas definitely has Merriam’s,” said Andrew Gregory, Ph.D, assistant professor in conservation biology and landscape ecology at the University of North Texas and lead researcher on this project. “Talk to others in Texas, and they’ll say they’re pretty sure what they’re seeing are Rios. The reality is we just don’t know.”

That uncertainty is exactly what a new research project from the University of North Texas aims to alleviate. Additionally, by pairing genetic analysis with regional breeding bird survey counts and published data on turkey survival and reproduction, researchers aim to better understand the trajectory of the region’s turkey populations.

Supported by the National Wild Turkey Federation and Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, this study is taking an innovative approach to answer these questions.

A few years ago, biologists conducted a large-scale effort to trap supposed Merriam’s in West Texas to gather data on population size and genetic purity. Despite weeks of effort, the trapping success was so limited that researchers walked away with almost no usable information. The turkeys simply weren’t showing up at net sites, and without birds in hand, biologists were left with nothing but educated guesses.

Gregory, who leads the new NWTF-funded study, decided to look at the problem from a new angle. Instead of attempting to capture birds, he and his team will collect genetic material left behind naturally on the landscape through scattered feathers beneath roosts, droppings on the ground after fly-down and occasional tissue or blood from samples already in hand. This innovative approach has been used in an additional NWTF-funded research project in Mississippi.

This genetic mark–recapture method eliminates the need to physically trap turkeys and offers a powerful, noninvasive way to understand exactly which birds are using a landscape and how many are present. Each feather or piece of scat carries a unique genetic fingerprint. By collecting and analyzing these samples across a region, researchers can identify individual birds, determine how many times they’ve been “recaptured” through additional samples and estimate the population with the same mathematical methods used in traditional banding studies — all without ever handling a turkey.

This genetic approach allows researchers to determine whether birds are pure Merriam’s, Rio Grandes or hybrids and to measure genetic diversity, lineage and the connectivity between different groups of turkeys across the landscape. In a place as vast and rugged as the Trans-Pecos region, where winter roosts can be difficult to find and live captures are notoriously unsuccessful, this method offers a realistic path toward understanding the true status of the region’s turkeys.

To make the process even more efficient, Gregory’s team will use drones during winter, when turkeys flock together and roost sites are easier to locate. Once a roost is found, researchers can visit it before fly-up, clear the ground of old feathers and droppings and return before dawn to collect the fresh genetic material the birds leave behind. Winter sampling provides the highest likelihood of finding large numbers of turkeys in one place, creating a clearer picture of population size and composition.

The genetic data is only the first step. Once researchers know which birds are present and where, they will integrate those findings into a broader population model using breeding bird survey counts and published data on turkey survival and reproduction from the region. The result will be an integrated population model capable of revealing whether turkey numbers are increasing, declining or holding steady. It will also help distinguish whether changes in population size are driven by local reproduction, immigration from surrounding regions or shifts in habitat quality.

This type of model gives wildlife managers something they have not previously had: a full picture of how Rio Grande and Merriam’s turkeys (if there are any) are actually functioning on Texas landscapes. If some areas show healthier or more genetically diverse populations than others, managers can begin examining what habitat factors or land management practices might be influencing those differences.

“Count data alone can be misleading,” Gregory explained. “You might think a population is healthy because numbers look stable, but maybe birds are constantly moving into the area while local reproduction is failing. The integrated model lets us see the whole story.”

Gregory emphasized that none of this work would be possible without the support of the hunting community. Turkeys across the country face challenges, and sustaining healthy populations requires good science, something hunters have always helped provide. Gregory expressed deep gratitude for NWTF’s role in making the work possible.

“I would just like to thank them for their support,” he said. “Turkeys are struggling, and we’re trying the best we can to figure out why, so we can do something about it. Their support is critical. We did this before — we reversed declines through research and management — and we can do it again.”

Gregory believes strongly that this project represents the next step in that long conservation legacy. It is an opportunity to finally understand what is happening with Merriam’s in Texas, to evaluate the health and future of the state’s turkey populations and to help guide meaningful management decisions for decades to come.

Fieldwork begins this winter, and over the next several years the University of North Texas team will gather the most comprehensive dataset ever assembled on Texas’ Merriam’s and Rio Grande populations. When all the genetic and demographic pieces come together, Texas will finally have the clarity it needs, and turkey hunters will have a deeper understanding of the birds that make this state one of the most remarkable turkey hunting destinations in the country.

Through its National Request for Proposals Program, the NWTF invested in this project along with eight other wild turkey research projects across the United States, totaling $503,618, for the organization's 2025 research investment. Since 2022, the NWTF and its partners have combined to put more than $22 million toward wild turkey research.

Thanks to support from dedicated volunteers and partners — such as the Bass Pro Shops and Cabela’s Outdoor Fund and NWTF state chapters — the NWTF’s RFP Program is an aggressive, annual effort to fund critical wild turkey research projects nationwide.