Relationships and Ratios

The sample size of research is building to uncover more about wild turkey behavior among relatives and the sex ratios among birds.

A common joke in the science field says biologists can be separated into two groups. First are the “squeezers” who want to go catch (squeezing, get it?) critters and follow them around and see what they do. Then there are the “smashers,” those who want to study the genetics and internal workings of critters. This relates to smashing a glass cover over a sample on a slide. No scientist falls strictly into either camp. Research questions often necessitate both approaches.

Historically, I prefer catching and tagging wildlife as opposed to hunkering down in a lab moving specimens through machines; however, informative science can certainly come from lab work. As such, I wanted to look at a couple of recent wild turkey projects that are combining data from both squeezing and smashing in support of conservation and management efforts.

Who’s related, who’s not?

Early genetic work on wild turkeys focused on lineage and subspecies designations. Restoration, though, saw wild turkeys translocated all over the U.S. This caused mixing of the subspecies. In truth, this hybridization is largely irrelevant to management. Wild turkeys generally operate biologically the same regardless of what subspecies or mixture they are. We typically don’t set up regulations differently at the subspecies level. Exceptions here include the Gould’s subspecies in Arizona and New Mexico and the Easterns and Rio Grandes in Texas, where harvest regulations are subspecies specific.

One of the most interesting genetic tools wild turkey biologists use today is the ability to build relationship databases between individual birds over time and space. They combine that data with GPS information collected from every turkey captured and tagged.

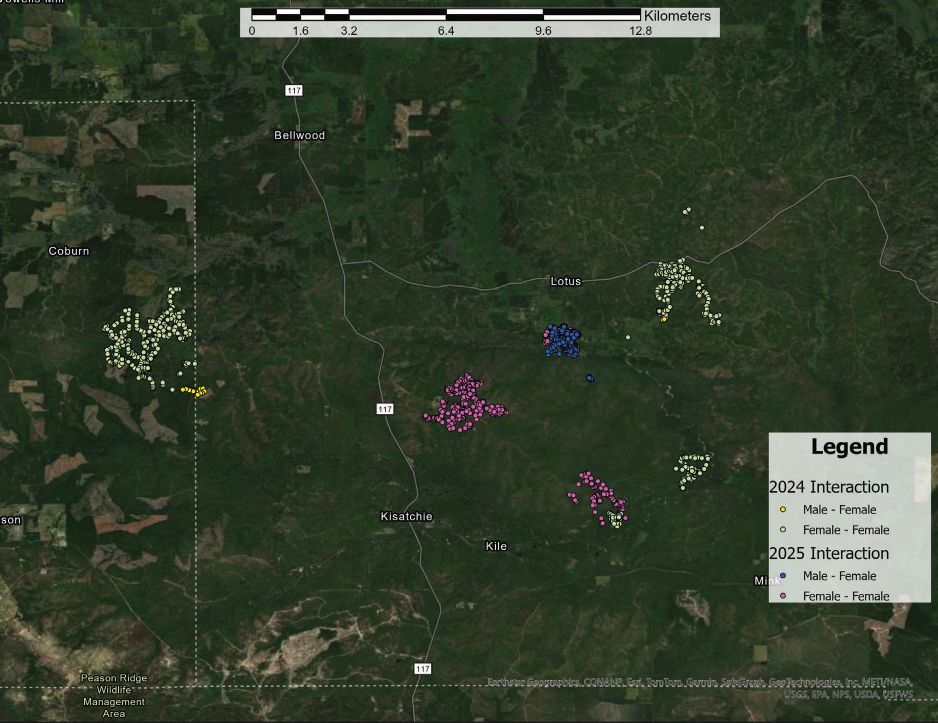

For example, Rachel Price, one of my students at Louisiana State University, is doing neat work for her master’s thesis focused on when and where male and female wild turkey individuals interact during the seven-day period before the females initiate their nests. She is discovering that the rate of interaction changes depending on how closely related individual birds are to each other. Nearly all interactions are between distantly related individuals. Very few are between siblings or parent-offspring. This makes sense. During the period right before breeding you probably don’t want to be near your relatives. Interestingly, the adage that most flocks are comprised of somewhat-related individuals doesn’t seem to hold true in the west Louisiana sites being studied. Most females in the flocks we catch are cousins at best.

Driving home the importance of habitat type to reproduction, nearly all interactions we see between males and females in this seven-day window before the females begin nesting, occur in open, early successional habitats: grasslands and field borders, areas where prescribed fire is recent and the understory is open.

Chromosomes and sex ratios

What little we know about sex ratios of wild turkeys can be summed up from two papers, including one I wrote in 2008 about Rio Grande wild turkeys in Texas. We found that about 56% of the eggs in clutches were male. Work in 2025 from Dr. Erin Ulrey at the University of Georgia found that the proportion of males in Eastern wild turkey clutches was about 38%. Basically, my 2008 work found that sex ratio of clutches was about 50:50, or one male for every female. While Ulrey’s work didn’t show that 1:1 ratio, breaking it down by the site studies is interesting. When you look at sites where hunting occurred, the sex ratio was skewed toward fewer males. At sites where hunting did not occur, the sex ratio was primarily one male per female in each clutch.

Thinking back to my Texas work, most of my study areas in the Hill Country did not allow turkey hunting, so it makes sense that unhunted areas showed balanced sex ratios.

Right now, you may be wondering about the implications of unbalanced sex ratios. Frankly, the sample size of research is small, and too much is unknown at this point. We need to continue looking for additional confirmatory data, just like scientists are supposed to do.

Next, many things can cause sex ratios to look skewed but not be. For instance, clutch sizes could be incomplete like they were in both studies. Maybe one or two eggs were missed because they were broken or eaten. That could have evened things out. Next, as Ulrey noted clearly in her work, there are many factors that can impact offspring sex ratio, including breeding timing, female body condition, embryonic mortality, unfertilized eggs, and the fact that birds can adaptively change the sex ratio of their offspring.