A 1,500-Mile Collaborative Effort

The National Wild Turkey Federation and cooperating partners are addressing critically important riparian areas in the Great Plains through the Waterways for Wildlife Initiative. This comprehensive, landscape-level effort by the NWTF focuses on riparian ecosystems found alongside rivers and streams, and their floodplains, within a 10-state region.

These riparian ecosystems, with their fertile soils and often diverse vegetation, are essential to supporting wild turkeys and hundreds of other wildlife species. Healthy riparian corridors in this part of the country often include towering cottonwoods that provide critical roosting habitat for wild turkeys, as well as shrubs and grasses that support nesting, foraging and brooding.

“We’re trying to improve 75,000 acres of habitat along about 1,500 miles of streams in a region that essentially starts in Texas and New Mexico, and runs straight up to Montana and North Dakota,” said Jared McJunkin, NWTF’s director of conservation operations for the central region. “This includes public and private land where we’re building new partnerships through this riparian restoration work.”

Riparian zones along the waterways of the plains in the American West are often in poor condition, overrun with invasive species. Once invasive species establish a foothold, they often outcompete native vegetation. The degraded habitat also contributes to reduced water abundance and quality, with the invasive plants guzzling scarce liquid resources and delivering little, if anything, in the way of help for wildlife.

Riparian restoration practices include offsite water development to manage livestock access, spring enhancement, installing beaver dam analogs (BDAs), invasive vegetation removal, streambank restoration, grazing infrastructure, tree and native vegetation plantings, conservation easements, and land acquisitions, among other options.

East of the Rockies, blizzards of fluffy cottonwood seeds drifting across the landscape during late spring and summer are a familiar sight. This rapidly growing tree species is a foundational building block of the native habitat wild turkeys require to prosper in the Great Plains.

“For wild turkeys in that part of the world, these tree areas are critically important,” McJunkin said. “We’re losing some of those cottonwoods.”

A major challenge associated with cottonwoods is the complexity with which they spread and grow. McJunkin explained that cottonwood seeds must land on and germinate in bare soil. Those soil condition results from some kind of disturbance, typically through flood events. Yet, manmade interventions along important waterways have reduced the frequency of naturally occurring floods for decades. Changing weather patterns, including heat and drought, are also exacerbating matters.

“If you do get the soil disturbance, then you need to catch the rain at the right time, to let the seeds germinate,” McJunkin said. “Once seedlings are established, they have to avoid being eaten by livestock or wildlife. They also can’t get hit by another flood prior to their roots setting or they’ll be wiped out. It’s an uphill battle for cottonwoods.”

Nonnative saltcedar and Russian olive, along with native, but negatively pervasive eastern red cedar, all compete directly with cottonwoods. While invasive cedars might provide some thermal cover in cold winter months, they rarely provide an adequate roosting option for birds. Helping cottonwoods flourish is the ticket for turkeys to thrive in these areas.

Managing Invasives

Invasives are managed via a variety of methods, depending on the species. Each scenario features slightly different approaches.

NWTF District Biologist Clayton Lenk, who oversees projects in the Waterways for Wildlife northern territories, explained that invasive species such as Russian olive corral an abundance of nutrients in the root system. When they’re cut, the remaining portion rapidly uses those stored nutrients for stem production. In short, they’re tough to kill.

“Luckily, conifers such as cedars don’t stump sprout, so they can be ground down with mowing heads and things like that,” Lenk said. “You don’t really have to worry about them later. Leaved trees, however, will stump sprout. We can’t just cut and let them lay. That doesn’t really take care of the problem. Deciduous species (those than shed leaves annually) are treated with herbicide to kill them.”

Numerous factors, such as the location and size of the targeted species along with the soil type, determine which herbicide application and equipment is used. Sometimes, terrain restricts use of mechanized equipment. The work then becomes more direct, with backpack sprayers, hack and squirt applications for individual plants, or chainsaw crews the only feasible options.

“Saltcedars often require a foliar chemical treatment, but after they die off, we have to deal with the skeletons,” McJunkin said, adding that the plant skeletons are later mulched. Saltcedar (or Tamarisk) release salts into the surrounding soil, delaying the growth of other plants. This helps managers see any plants that were missed in the original treatments.

NWTF District Biologist Annie Farrell focuses on the southern half of the region covered by the initiative. There, mechanical removal of eastern red cedar followed by prescribed fire treatments is the preferred course.

“We help fund the mechanical removal,” she said. “The agency that received the funding then comes in behind and does the burn.”

The prescribed fire removes any residual woody biomass and kills saplings that may have been missed during the mechanical treatment. A regimen of fire every few years knocks back unwanted woody encroachment before the bark on the stems gets thick enough to create a fire-resistant barrier.

A lack of fire, plus the fact that livestock don’t enjoy the unpalatable flavor of invasives such as cedar and Russian olive, contributed to the spread of these undesirables.

Build a ‘Collaborative’

McJunkin said the NWTF is knowledgeable in best management practices and readily shares this expertise with partners. Ultimately, the aim is to get the job done, economically and effectively.

Partners include an array of nongovernmental entities, including Trout Unlimited, Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, Mule Deer Foundation, Pheasants Forever and Ducks Unlimited, plus state and federal wildlife agencies.

The Waterways for Wildlife Initiative is a continuing example of how volunteer work, fundraising efforts and more translate into NWTF staff expertly engaging conservation partners and private landowners across the country to improve wild turkey habitat.

“That’s the other idea behind this – to build a collaborative across a 10-state area,” McJunkin declared. “We want to prioritize funding across our focal landscapes and have partners identifying projects that make collaborative sense. Everybody is on the same team and bringing something to the table. The time is now!”

NWTF, Partners Allocate over $16 Million for 2024 Waterways for Wildlife Projects

The NWTF’s Waterways for Wildlife Initiative marks its third year of funding vital waterrelated conservation projects with a $225,000 investment in 17 high-priority conservation actions in America’s Great Plains. Conservation projects funded by the NWTF initiative will address conservation needs in riparian ecosystems (areas situated along creeks, streams and rivers). Altogether, partners are investing nearly $16.2 million in the 17 new Waterways for Wildlife projects this year. Projects slated for 2024 will enhance over 60 stream miles, nearly 5,750 acres of riparian habitat and more than 16,400 adjacent upland acres.

“We are proud to make another significant investment in the water health of our country’s vital Great Plains ecosystems,” said Jared McJunkin, NWTF director of conservation operation for the central region. “Our Waterways for Wildlife team diligently ranked and scored projects, ensuring our investment has the greatest impact on our nation’s natural resources, and we are once again elated to see Waterways for Wildlife bring in diverse stakeholders rallying for the common good. Everybody appreciates clean water and healthy habitats.”

Waterways for Wildlife’s 2024 announcement comes off the heels of two solid first years for the initiative and its partners, including 2022’s $2.8 million investment in 14 projects and 2023’s $5.3 million investment in 20 projects.

Ogallala Aquifer Benefits from Riparian Restoration

Deep beneath the 10-state Waterways for Wildlife Initiative territory, the vast Ogallala Aquifer provides lifegiving groundwater to the often-arid high plains landscape.

“For the longest time, most people thought this aquifer would never go dry, and now we’re finding that it’s losing depth in some areas,” McJunkin said. “This is very concerning because the aquifer is what keeps livestock and agricultural producers out on the landscape and provides water for wildlife. Depletion of the aquifer has many implications on a social, economic and even community level. The aquifer makes a livelihood possible, supporting local communities and economies.”

Encompassing roughly 174,000 square miles, the Ogallala Aquifer is one of the planet’s largest. Its depletion would be disastrous on many levels. According to McJunkin, some farmers are already facing the decision to retire wells, lower agricultural water consumption, or swap irrigated crops for those more tolerant of arid growing conditions.

Riparian restoration efforts across the Great Plains help recharge groundwater and improve water quality, while also alleviating the aquifer’s decline by eliminating thirsty invasives that compete with native cottonwoods.

“We’ve removed invasive species where the aquifer is impacted, especially through Kansas, Oklahoma and Nebraska. These species are sucking up a lot of the water table – they just weren’t there before,” McJunkin said. — J.A.

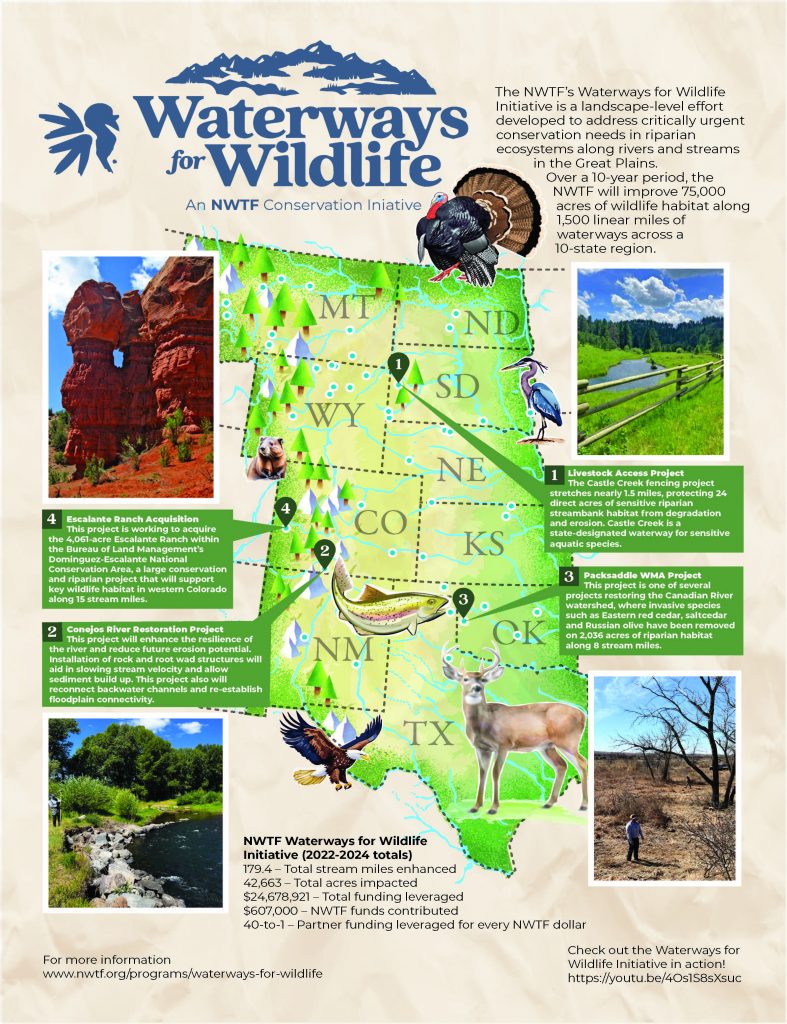

An NWTF Conservation Initiative

The NWTF’s Waterways for Wildlife Initiative is a landscape-level effort developed to address critically urgent conservation needs in riparian ecosystems along rivers and streams in the Great Plains.

Over a 10-year period, the NWTF will improve 75,000 acres of wildlife habitat along 1,500 linear miles of waterways across a 10-state region.

For photos below, reference illustration above with corresponding number.