Behind The Bird: History And Conservation Of The Gould’s Wild Turkey

Unraveling the mystique of the Gould’s subspecies, the Southwestern desert’s turkey treasure.

I reached the small cattle water catchment, nestled deep into a rugged ravine, and there it was — a hidden gem shimmering with water. My heart leapt with joy, for this was the very spot I scouted on Google Earth, but there was no way to know if it would hold water this year. As I approached the wet ground, a silent plea involuntarily escaped my lips, “please be here.”

At the water’s edge, deeply embedded in the mud, was the grandest turkey track I had ever seen and visions of a gargantuan tom filled my mind. I slowly circled the area to look for more sign.

On the opposite side of the catchment, I found fresh tracks and wing drag marks adorning the powdery dirt, narrating an unseen dance. Unable to stop myself, I let out a pleading five-note yelp sequence. A low, thunderous gobble echoed back at me in response, likely not more than a hundred yards away.

Panic set in as I realized my rookie mistake of not having a blind spot chosen before calling. My eyes darted around, seeking salvation in the form of a natural blind. I spotted a triple-trunked alligator juniper, its base masked in shade — it was my best option. Quickly, I nestled into the makeshift blind, propping my gun on my knee, aware that the slightest mistake could ruin my chances at a once-in-a-lifetime bird.

I wish this gobble-filled climactic hunt wasn’t a lie, but it is. It’s complete and utter hogwash.

But truth, my friend, stands as resolute as the cliffs of time — this grand vision, a beguiling lie, a dream dancing just beyond my grasp. Like countless hunters, the elusive Gould’s turkey remains a wily ghost, ever escaping my eager pursuit. The fickle hand of fortune has yet to deal me the winning cards for such an expedition, and my humble pocketbook holds no golden ticket to this grand adventure. But the daydreaming continues.

Gould’s turkeys are the heavyweight contenders among the five turkey subspecies. Males weigh an average of 20-25 pounds, while hens come in between 8-12 pounds. They also boast the title of having the largest feet, longest legs and longest central tail feathers.

Although Gould’s physical size, beauty and tail will impress, their spurs and beards often come up short in the length department. An average tom’s beard will measure 8½ inches, and his spurs will probably be less than a half-inch. Gould’s tend to rub both their spurs and beard down in the steep rocky terrain. It’s not uncommon to come across an old tom with nothing but small nubs.

Their overall blue-green iridescence is noteworthy, but it’s their white-tipped tail fan and tail coverts that steal the show. Picture Merriam’s, but cranked up a couple of notches in the white department. Their gobble is distinctly lower in pitch, and some hunters claim they can feel their gobble as much as they hear it. Gobbling activity usually peaks in late April and commonly continues into early June. While their gobble is distinctly lower, their putts are higher pitched than any other subspecies.

Gould’s are known for their shy and elusive behavior which adds to their allure. Compared to some other turkey subspecies, they are generally warier and less accustomed to human presence, making spotting them in the wild a rare and cherished experience.

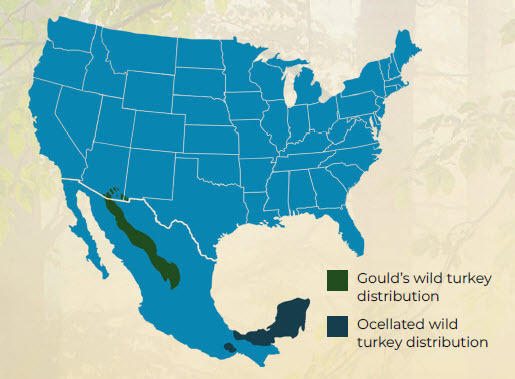

Gould’s turkeys can be found in the far southwestern corner of New Mexico, the adjacent southeastern corner of Arizona and northern Mexico. In both states, you’ll encounter them at elevations ranging from 4,500 to 6,500 feet. The combined Gould’s population in the U.S. is estimated at around 1,200 birds, though this number likely underestimates due to the difficulty of counting birds on private lands.

In 1974, the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish listed Gould’s as a threatened species, leading to research, translocations, habitat priorities and spring gobbling surveys. The successful 2022 delisting in New Mexico opened up additional hunting opportunities, with four once-in-a-lifetime draw tags offered in 2023 for the spring season.

Efforts to re-establish Gould’s turkey in southeast Arizona began in the 1980s, with more than 280 birds translocated from Mexico to Arizona between 1997 and 2006. NWTF staff and volunteers played a crucial role in the process, constructing quarantine facilities and monitoring the turkey conditions and equipment.

Gould’s natural dispersal in both Arizona and New Mexico is uncommon, as they inhabit isolated islands of habitat surrounded by inhospitable deserts. This makes genetic mixing a topic of interest and one of the main reasons for in-state translocations.

Most of the mountain ranges occupied by Gould’s turkeys run north to south, resulting in east- to west-running ravines and valleys. North-facing slopes in these valleys receive less direct sunlight, leading to increased soil moisture and larger trees, making them the preferred roost sites for Gould’s. Roost site availability is one of the main limiting factors for Gould’s populations.

Gould’s will roost in cottonwoods, ponderosa pine, Emory oak, Arizona walnut and Arizona sycamore. They seem to have a preference for roosting in Chihuahua pine if available. Gould’s have high site fidelity to their roost sites and will usually roost in the same grove of trees for an extended period of time.

Despite being the least researched among the subspecies, efforts are underway to change that narrative. Recent research projects have focused on Gould’s habitat use, limiting factors and reproduction. In the summer, the Gould’s diet revolves around juniper, manzanita and oak, and then it slowly shifts toward primarily grass seed in the winter months.

Gould’s average clutch size is 5.6 eggs, which is half that of other subspecies. They are also the last to initiate nests, aligning their reproductive period with the monsoon rains that come from late June through September, bringing more than 50% of the area’s annual precipitation and providing essential greenery and insect production to the region.

As you can probably imagine, water is the most significant limiting factor for Gould’s population growth. Water dependency is especially apparent when looking at nesting and brooding movement. Nests are almost always found within a couple hundred yards of permanent water and brooding centers around wide open valleys close to permanent water. In these valley bottoms, poults’ main escape cover is bear grass. Gould’s use any water source they can from natural riparian areas to cattle troughs. The NWTF has partnered with the USDA Forest Service to protect and enhance multiple riparian areas and water features for the benefit of Gould’s turkeys.

The future outlook for Gould’s wild turkeys is promising, a true conservation success story. We owe this positive outlook to the cooperation of government agencies, conservation organizations, landowners and, above all, the dedicated volunteers whose blood, sweat and tears have spearheaded their preservation.

Gould’s Range

The Gould’s subspecies (Meleagris gallopavo mexicana) is hunted in two states (with appropriate, difficult-to-acquire tags) and in Mexico. In 1856, John Gould, an English ornithologist, collected the first recorded Gould’s turkey specimen in Mexico.

CHARACTERISTICS

- Long legs similar to the Osceola

- Snow-white tips on tail feathers and upper tail coverts

- Wings are moderate in coloration

- Adult males weigh 18 to 30 pounds (Heaviest recorded in NWTF Wild Turkey Records: 29.375 pounds)

- Adult females weigh 12 to 14 pounds

- Moderate gobbles

- Moderate beard lengths

- Shortest spurs of all subspecies

A Different Species: The Ocellated turkey

The Ocellated turkey (Meleagris ocellata) is a fascinating and lesser-known species (not a subspecies of the North American wild turkey) found in the dense forests of the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico, Belize and northern Guatemala. Unlike its more widespread relative, the wild turkey, the Ocellated turkey boasts a strikingly different appearance and unique behaviors. Males boast a crown which looks like a small chicken’s comb with yellow Nerds glued all over it, the more Nerds the better.

One of the most distinctive features of the Ocellated turkey is its iridescent plumage, which gleams with a spectrum of colors, including bronze, green and gold. Males exhibit beautiful, eye-catching feather patterns with “oscillated” eyespots on their tail feathers, resembling intricate peacock-like designs. Females, although less vibrant, still display an impressive range of colors.

Ocellated turkeys are beardless, but they make up for their lack of a beard with exceptionally long spurs. Spur lengths average over 1½ inches and can go over 2½ inches (longest recorded in NWTF Wild Turkey Records is 2.875 inches).

In terms of behavior, Ocellated turkeys have some differences from other turkey species. They are more arboreal (inhabiting trees often), and they have a distinctive, high-pitched call that sets them apart from the familiar gobble of their cousins. They primarily feed on a diet of fruits, seeds, insects and small reptiles, contributing to their role as important seed dispersers in their ecosystems.

Due to habitat loss, hunting and fragmentation of their forested habitat, the Ocellated turkey faces conservation concerns. Recognizing its ecological importance and unique beauty, efforts are underway to protect and conserve this enchanting bird species, ensuring its survival in the wild for future generations to admire and appreciate.