Behind The Bird: History And Conservation Of The Merriam’s Wild Turkey

Frost blanketed the rolling fields in eastern Montana when I harvested my first Merriam’s wild turkey. It was cold enough that my breath swirled like white smoke, and my numb fingers could barely feel my shotgun through thin gloves.

I wasn’t targeting turkey per se on that chilly October morning. They were one of a number of gamebirds that were in season, including pheasant, sharp-tailed grouse, grey partridge, and the waterfowl coming and going around the potholes in the area. Every fall, my husband, Jack, a few friends and I gathered at our favorite campground for this multi-species quest.

As we headed toward a patch of prairie where we typically found sharp-tails, Jack spotted a half-dozen Merriam’s wild turkeys pecking along the edge of a shallow ravine. Cottonwood trees grew out of the depression, perfect for turkeys to roost in, while also providing us with cover to sneak up on these wary birds. We entered the ravine a quarter-mile away, then quietly approached them, stepping carefully to avoid snapping a twig underfoot. Using a low bush as a marker, we crept up the side of the ravine. My heart pounded. I no longer noticed the cold. I knew the skittish turkeys were on the other side of the bush. “Ready?” Jack whispered. I clicked off the safety and nodded, “Yes.”

Together we rose up and shot, bagging his and hers Merriam’s. It was the highlight of the hunting trip, yet it was an experience that would not have happened 70 years ago.

History and Range

Merriam’s wild turkey were named for C. Hart Merriam, the first chief of the U.S. Biological Survey. Though indigenous to ponderosa pine forests of Arizona, New Mexico and Colorado, the subspecies did not exist in Montana or the rest of its current range, a total of 14 states, prior to the mid-20th century. They’re a turkey success story due to trap-and-transfer programs. For example, in 1954, Montana imported 13 Merriam’s from Wyoming, followed by 18 in 1955 and then 26 more in 1956 and 1957. The turkeys were released in three locations in the central and eastern parts of the state. All other releases in Montana were the offspring of these initial birds, plus a few more from Nebraska. The last release was in the early 2000s. Today, there are approximately 120,000 Merriam’s wild turkeys in Montana.

“They’ve adapted and are doing well,” said Brian Wakeling, Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks’ Game Management Bureau chief. “Their success in northern areas like Montana is due to artificial food sources during the winter months, especially durable grains, like corn and wheat, where livestock is fed. If they have access to food, they’ll get through the winter … Turkeys like to live where food and water is easy to come by, such as river valleys, just like we do. The more we enhance a place, the more turkeys like it, too. On the plains, we plant trees as wind breaks. Turkeys need trees for roosting. It makes it possible for them to live there. And with us as neighbors, they have lower risk of predation.”

I can attest to the success of Merriam’s wild turkeys in Montana. Where I live, in Red Lodge, they strut fearlessly through neighborhoods, cluck around public parks and roost in the trees along the local creek. That’s the good news.

Threats and Conservation

The bad news is that Merriam’s wild turkeys are susceptible to long-term drought and catastrophic wildfire, which have become increasingly prevalent in the West. Drought impacts the health of Western forests and riparian areas, making them less resistant to wildfire. Wild turkeys can tolerate moderate natural fire, and even like it, because of the feast of bugs, small reptiles and early successional berry-producing plants that emerge after the fire. Over the last decade, though, as summers have become warmer and drier, wildfire season has become longer with more catastrophic wildfires destroying thousands of acres of turkey habitat.

Too much rain at the wrong time can be devastating, too. In the northern Rockies, it’s common for a cold snap, even snow, to follow a spring rainstorm.

“If it’s really wet, young poults can die of hypothermia,” Wakeling said. “They don’t have enough feathers yet. They lose more energy trying stay warm than they gain by eating.”

However, catastrophic wildfires remain a much bigger threat.

What You Can Do

The saying, “fight fire with fire,” certainly applies when it comes to conserving the Merriam’s wild turkey in upland ponderosa pine forests, the habitat in which Merriam’s evolved.

“When forests are over-dense, they become tinder pots,” said Collin Smith, NWTF district biologist in Montana, Wyoming and Idaho. “We work with forest owners, both public agencies and private landowners, to better manage their forests. Landowners are usually willing to thin trees that have commercial value — trees at least 9 inches in diameter — but for smaller stuff, they aren’t motivated or can’t afford to do it. But you need to remove the dog-haired growth to provide more sunlight, water and space for healthy trees to grow. We do that through prescribed burns. You also need to put fire in the system to create fire resilience.”

As an example, this summer the NWTF helped with forest thinning via controlled burns in Bitterroot National Forest to take out noncommercial-grade trees.

Improving the health of riparian areas requires a different strategy.

“Cottonwoods, which are critical for Merriam’s wild turkeys, are in decline because dams wreak havoc on the natural flood regimes that cottonwoods need, and because of grazing patterns,” Smith explained. “Cattle love river bottoms for shade and water, but they denude the vegetation. Yet, cattle can be a tool in riparian health. It’s all about when the cows are there and for how long. We help ranchers develop riparian pastures that properly time grazing.”

That’s a surprising concept, and one that’s winwin for ranchers, Merriam’s wild turkeys and all wildlife that depend on riparian ecosystems. It’s site specific. In some places, like along the Yellowstone River where the cottonwoods are multi-aged and healthy, it’s better to graze cattle along the river early in the growing season so they can feed on new green-up, then move them. In other places, where the cottonwoods are the same age and dying, and there’s no regeneration, it’s better to graze cattle there in the fall after the leaves drop, to give seedlings a chance to establish.

Riparian areas in the West are also highly susceptible to domination by nonnative plants, like Russian olive and salt cedar. While Merriam’s wild turkeys will eat Russian olive fruit, it lacks the nutritional value of native soft mast, like chokecherry, currant and silver buffalo berry, that Russian olive pushes out. In Montana, the NWTF has implemented programs to help remove nonnative plants along the Yellowstone, Powder, Milk and Missouri rivers and around Fort Peck Dam.

Even native species, like juniper, can crowd out other native plants when an ecosystem is out of balance, which brings us back to the need for prescribed fire. Minus fire control, junipers can take over, so the NWTF has implemented a program in the headwaters of many streams in Wyoming’s Bighorn Mountains to remove junipers, which in turn, sends more precious water downstream, helping to mitigate drought.

“We work to improve the health of the ecosystems where Merriam’s wild turkey live,” Smith said. “It helps benefit all other species that use those systems, too.” Including you and me.

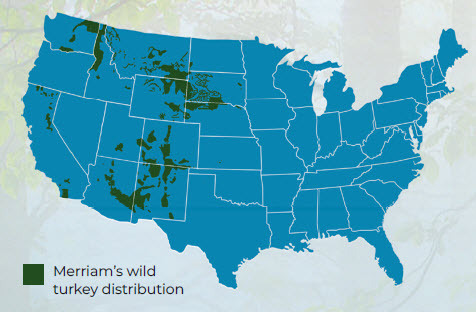

Merriam’s Range

The Merriam’s subspecies (Meleagris gallopavo merriami) is hunted in 14 states and some Canadian provinces.

CHARACTERISTICS

- Snow-white tips on tail feathers.

- More white and less black on wings.

- Adult males weigh 18 to 30 pounds (heaviest entered in NWTF Wild Turkey Records: 31.5 pounds).

- Adult females weigh 8 to 12 pounds.

- Weakest gobbles of all subspecies.

- Shortest beards of all subspecies.

- Shortest spurs of all subspecies.

More About Merriam’s

Native Americans on the Colorado Plateau and desert Southwest domesticated the Merriam’s wild turkey for food and for its feathers. They placed the feathers on their arrows and wove them into cloaks, sandals, blankets and other textiles. They used the hollow bones for whistles, containers, beads and other trinkets.

In the 1970s, Colorado traded Merriam’s wild turkeys to Idaho in exchange for 40 mountain goats that were introduced atop Mount Evans. Both species have flourished in their new homes.

Merriam’s wild turkeys are not the only creature named after Clinton Hart Merriam. Ninety-nine mammals, including a lizard, elk (extinct), mouse, chipmunk and ground squirrel, are also named for the first chief of the U.S. Biological Survey.

Merriam’s and Gould’s wild turkeys look similar, with their white-tipped fans; however, the tail margins on a Merriam’s wild turkey are not as pure white nor as wide. Merriam’s are comparable in size to the Eastern wild turkey. Gould’s are larger, with longer legs, larger feet and larger central tail feathers.