Behind The Bird: History And Conservation Of The Rio Grande Wild Turkey

From the central plains to the West coast, the Rio Grande subspecies has found a home.

They say it’s the ones that get away that you remember. That was certainly true on a hunt in South Texas 10 years ago.

The prickly brush country was just waking up on a cold spring morning. Gobbles filled the air at every point on the compass. Down from their roost, I heard multiple gobblers sounding off, but I could not see them through the thick mesquites. Drumming and puffing, wings dragging the parched ground, the tease was unbearable. I sat ready with a camera and a bow.

Finally, they stepped from the brush into a clearing 50 yards away. Not one, not two, not three, but 10 giant Rio Grande gobblers, each one in a full strut following three dust-colored hens. The slanting light of early morning illuminated their bronze-colored tail fans like a spotlight. The lead tom was as big as a washing machine. I poked my long-lensed camera out of the blind. When the camera refused to turn on, my mood sank. I left the camera’s battery on a charger back at camp. I watched the show, 10 longbeards in full strut, showing off in pristine light conditions for five minutes. They were too far for a bowshot and refused to come closer. Finally, they swerved back into the brush, avoiding my hen decoy to follow the real deal. I wish I had the pictures to prove it.

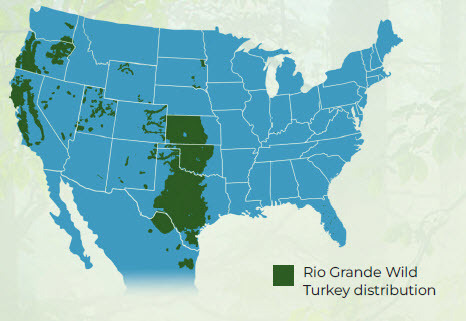

Map of the Rio Grande

Thousands of hunters love to hunt Rio Grande turkeys. Rio Grande turkeys can be found in the central plains and on the west coast and points in between. States like Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas boast good numbers. California, Oregon and Washington are home to Rios as well. They even show up in unexpected locations like northeastern New Mexico, eastern Colorado, Nevada and Utah.

Jared McJunkin, director of conservation operations in the central U.S. for NWTF, provided details on the Rio Grande subspecies expansion over the past 50 years.

“Since the Rio Grande subspecies is tied to riparian corridors and adjacent shrublands and grasslands, expansion typically happens at the subpopulation level along riparian corridors, with birds expanding out further into adjacent landscapes when suitable roosting habitat is available,” he said. “During restoration efforts, Rio Grande wild turkeys were moved from source populations in states like Kansas and Oklahoma further west to states like Utah and Wyoming. These movements were aimed at either bolstering existing populations or establishing new populations in areas of these mountain states more suitable to the Rio Grande subspecies than the Merriam’s subspecies. Many of these trap-and-transplant efforts resulted in rapid expansions of wild turkeys, resulting in huntable populations today.

“For the Rio Grande subspecies, much of the NWTF’s focus has been on riparian (streamside) restoration, as riparian areas provide critical roosting habitat in an otherwise grass- and sage-dominated landscape. In 2022, the NWTF launched a new initiative, called the Waterways for Wildlife (W4W), with an increased focus on riparian restoration efforts across a 10-state area, extending from New Mexico and Texas north to Montana and North Dakota. The Rio Grande subspecies can be found in nine of these 10 states. The work the NWTF and its partners are doing through the W4W initiative will directly impact critical roosting habitat.”

Texas could be considered the epicenter of the Rio Grande subspecies. Jason Hardin, wild turkey program leader at Texas Parks and Wildlife, gave a history lesson on the Rio Grande in Texas.

“Today, Texas is blessed with a robust Rio Grande wild turkey population across almost all landscapes with suitable habitat. However, there was a very dark period for wild turkeys in Texas. Subsistence and market hunting was rampant with the arrival of European settlers. Wild turkeys were a popular source of protein and readily available in the mid-1800s; however, these practices quickly resulted in extirpation of the bird across most of its range in Texas by the 1880s.

“The Texas legislature placed hunting regulations in the late 1800s to try to protect the bird. Unfortunately, the earliest hunting regulations were extremely liberal, and there were no game wardens to enforce even the liberal regulations. The earliest regulation was in 1897 outlawing trapping for five months of the year. In 1903, a 25-bird-per-day bag limit was established. Obviously, the early regulations were unsustainable, which begs the question, just how many birds were being taken prior to these regulations. The lack of enforcement of regulations was also an issue and many individuals undoubtedly continued to remove large numbers of birds in the decades that followed. It wasn’t until 1919 that a limit (of three bearded gobblers per season) was established. The addition of game wardens in the 1920s to enforce regulations also paid dividends and populations began to rebound with the help of conservation-minded landowners. Around this time, the Game, Fish, and Oyster Commission, predecessor to TPWD, estimated an all-time low of about 100,000 wild turkeys in Texas and only found in strongholds in north Texas (Concho and Coleman counties), the Edward’s Plateau and South Texas’ Coastal Sand Sheet. This probably made up most wild turkey populations in the U.S. at that time.

“Since the 1920s, TPWD has restocked over 30,000 Rio Grande wild turkeys. The effort has been a tremendous success, and, as of 2022, TPWD had an estimated 600,000 Rio Grande wild turkeys across the middle of Texas from the Pecos River to I-35 and from the Panhandle south to the Rio Grande Valley.

“Drought has played a significant role on our turkey populations over the last few years, but we were still seeing big numbers just a few years back. A few consecutive years of above average rain and mild summer temperatures can get us right back on track in a lot of the Rio Grande wild turkey range.”

Texas Memories

I’ve hunted Rios in Texas, northeastern New Mexico and the Oklahoma Panhandle. I’ve had great hunts in all three states, but Texas is my home. When I think of Rios, I think of prickly pear cactus, rocky ground, dry air, windmills, rattlesnakes and white-tailed deer. I shot my first gobbler in central Texas in McCulloch County in 1986. Texas has a fall and spring season. Today, a hunter can take a total of four turkeys per year, fall and spring seasons combined, in those counties with the highest numbers.

Texas Rios have provided an unexpected bond between my 15-year-old daughter, Emma, and me. Since Emma was small, she has been fascinated by wild turkeys. Her favorite food on planet Earth is fried wild turkey nuggets. Emma has already shot 10 gobblers in her young life. Wild turkeys give a middle-aged man and a teenage girl something to talk about. That will always be the most important history of the Rio Grande turkey for me.

Rio Grande Range

The Rio Grande subspecies (Meleagris gallopavo intermedia) is hunted in 12 states, Mexico and Canadian provinces. Native to the central or intermediate region of North America, Rios are one of the five wild turkey subspecies in the states.

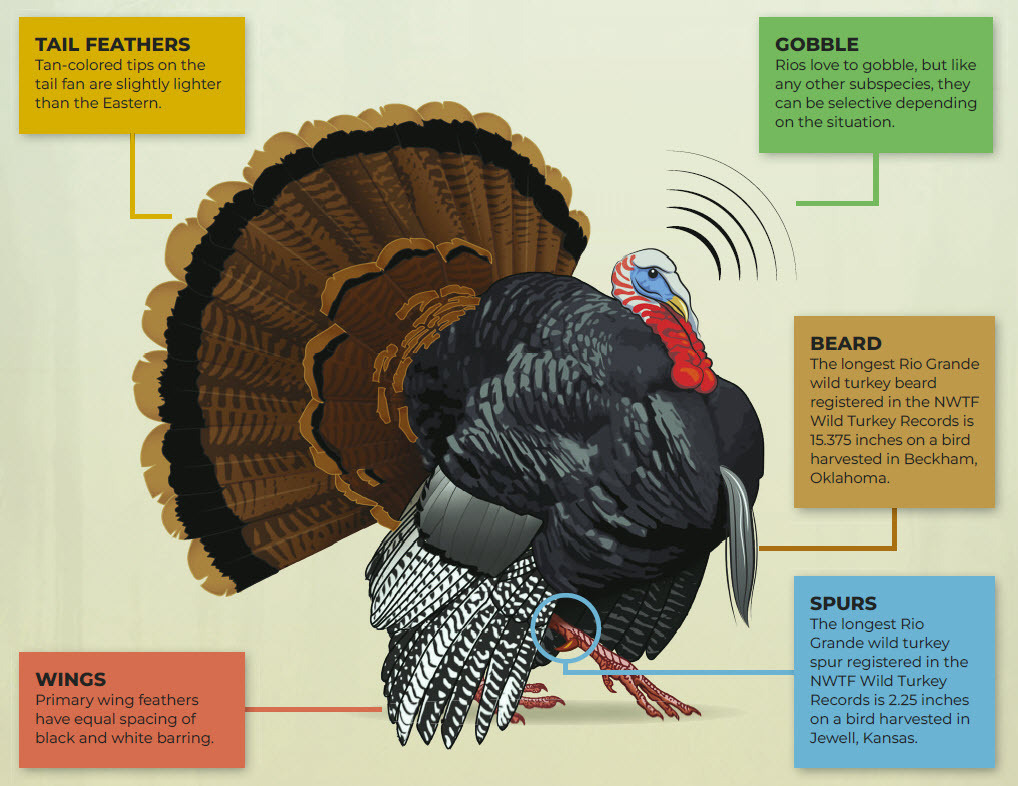

CHARACTERISTICS

- Tan-colored tips on tail feathers

- Same amount of black and white barring on wings

- Adult males weigh approximately 20 pounds (heaviest recorded: 37.125 pounds)

- Adult females weigh 8 to 12 pounds

- Moderate gobbles

- Moderate beard length

- Moderate spur length

Rio Grande Facts

The Rio Grande wild turkey is native to the central plains states and got its common name from the area in which it is found: the life-giving water supply which borders the brushy scrub, arid country of the southern Great Plains, western Texas and northeastern Mexico. They are distinguished from the Eastern and Florida subspecies by having tail feathers and tail/rump coverts tipped with yellowish-buff or tan color rather than medium or dark brown. Hens average 8 to 12 pounds while gobblers may weigh around 20 pounds at maturity.

The Rio inhabits brush areas near streams and rivers or mesquite, pine and scrub forests. It may be found up to 6,000 feet elevation and generally favors country that is more open than the wooded habitat favored by its eastern cousins. The Rio Grande is considered gregarious and nomadic in some areas, having distinct summer and winter ranges. It has been known to travel distances of 10 or more miles from traditional winter roost sites to its nesting areas. When suitable roost trees are scarce or nonexistent, Rios roost on man-made structures like power lines, windmill towers or oil storage tanks. — From NWTF Wildlife Bulletin No. 3 by Mary C. Kennamer