Unique Landscapes, Unique Solutions: Conserving Southern Utah’s Wild Turkeys

Clint Wirick of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recounts a unique wild turkey conservation story in southern Utah.

Location: Southern Utah

Partners: NWTF, Utah Chapter of NWTF, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Partners Program, Utah State University, Bureau of Land Management, Utah Division of Wildlife, Utah Watershed Restoration Initiative and Grand-Staircase Escalante Partners.

To start off transparent, I am not a turkey biologist, not an upland game biologist and only started turkey hunting late into my adulthood, but If you are here for a good story about curious conservationists and landowners in one of our country’s most unique area that wild turkeys inhabit, then stick around.

I probably need to restore my legitimacy as the writer of this article a little bit after that introduction. For my day job, I lead a program for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service working with private landowners who want to do good things for the land and wildlife. It’s called the Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program. I’m a wildlife biologist, and my specialty is habitat restoration and partnership building around conservation issues. Sometimes I pinch myself because I am truly living my childhood dream. I also love turkeys and turkey hunting. I didn’t discover this love until about 12 years ago, but it’s a passion of mine now, and whenever my job and my love for turkeys can co-mingle, I take the opportunity.

With introductions out of the way let’s get to the story. As with any good story, this one has a super cool setting, interesting plot, a conflict needing action and sets up a sequel.

The Setting

Our story takes place in and around what might just be the eighth wonder of the world in my opinion, the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in Utah. This place is epic. Slot canyons – narrow, twisting, turning paths carved into the rock by water and wind over the millennia. Vast desert plateaus covered in grasses, flowers, shrubs and junipers nicely framed by broken cliffs – a natural cathedral of sorts.

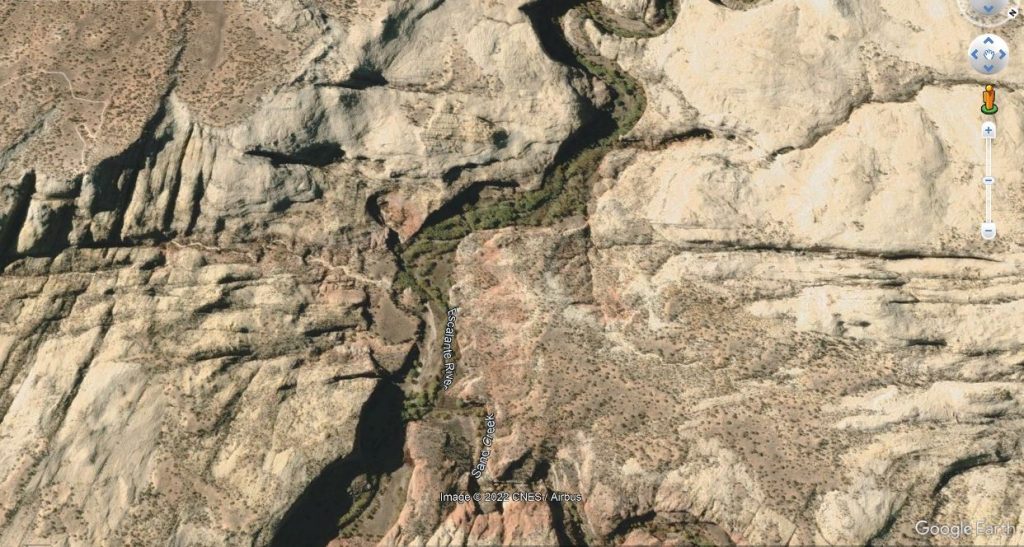

Today, the town of Escalante is the heart of the area, with a cultural mix of dusty beat-up ranch trucks and visiting Subarus. Agriculture and tourism are what keep this place alive economically. What really is the mother of all life here, though, is the wet artery of the Escalante River. A desert river, unencumbered by modern day dams. One of the last free-flowing rivers in the American West. From above, the Escalante River is a ribbon of green vegetation carved deep into the oranges and reds of desert sandstone.

If you’re wondering what all this southwest desert talk has to do with turkey habitat, you’re not alone. This place isn’t a typical wild turkey kind of place. But wild turkeys thrive here. The river is a ribbon of life cutting through a harsh environment. Like many wildlife species here, the river is life support.

The Plot

The plot of the story is this - the Escalante River had become invaded by non-native trees over the last several decades, primarily Russian olive. Sparing you all the ecological minutia, the moral of the Russian olive story is this: it became the dominant species on the river, outcompeting native vegetation and creating a situation where thick stands of this invasive tree were the only thing growing. The native cottonwoods, willows, buffalo berry, Indian rice grass, primroses and spike rushes were disappearing and being replaced by thick dark Russian olive forests with nothing underneath. It was also changing soil and water chemistry, a true ecological enemy.

A group of conservationists, landowners and government agencies got together around 2009 and decided to do something about the Russian olive disaster on this last great free-flowing river in the American Southwest. Since then, Russian olive has been removed from most of the 87-mile river corridor, giving way to blossoming native vegetation once again.

The Conflict

Our conflict was this - what will removing Russian olive do to the hundreds of desert dwelling wild turkeys. Two schools of thoughts existed: 1.) people were afraid removal of Russian olive was going to be bad for turkey populations, especially in the winter as some hypothesized Russian olive is an important winter food.

2.) Landowners were concerned wild turkeys would cause more crop damage (mostly alfalfa) in ag fields adjacent to the river if Russian olive was removed as a food source.

As a biologist, I had my answers based on what I knew about habitat/wildlife interactions. My opinion was, in the long run, removing Russian olive for native diverse habitat was way better for turkeys for several reasons we don’t need to dive into here.

The problem was, no research existed to back up these claims. Data explaining the effects on wild turkeys when converting river corridors habitat from one thing to another in a desert was simply non-existent. The situation here is so unique it’s kind of like a turkey unicorn.

The Action

With our conflict established it was time for action. We wanted to be able to give answers backed up with some science. Our solution was to gather the best team we could, beg for money and put some tracking devices on turkeys.

In the beginning, it was somewhat comical. None of us had ever done this before. We fumbled trapping birds and figuring out how to attach the GPS efficiently, effectively and comfortably, but we ended up being very good at it. We apologize to the first few birds for handling you too long, ha-ha. Using this GPS technology, the turkeys told us a lot about themselves through their movements and behavior.

Here are a few of the takeaways from this first-of-its kind research:

- Removal of Russian olive did not affect turkey roosting during the winter. Turkeys selected large cottonwoods in the river corridor near agricultural lands, regardless of whether or not Russian olive had been removed.

- Russian olive removal did not cause females to stop using an area during the winter, possibly meaning that Russian olive is not a critical winter food resource.

- During the summer, turkeys exhibited behavior of both Merriam’s and Rio Grande. Some migrated many miles into the high-forested elevations of Boulder Mountain as would be expected of Merriam’s. Others stuck to the lowland desert river corridor as would be expected of Rio’s.

- Females staying in the lowland desert river corridors are likely to be positively affected by Russian olive removal because literature suggests removing Russian olive creates better brood-rearing and shelter habitat by opening the forest floor, creating woody debri, and increasing shrubs, flowers and attracting more bugs.

- Anecdotal observations of turkey groups by researchers, technicians and wildlife biologists showed turkeys using areas treated by Russian olive. Making inferences from observations demonstrates Russian olive removal did not negatively impact turkeys.

The Sequel

Three plot scenarios would make for a great sequel and follow-up to this story:

1. Genetic research to understand what and who these birds really are. We captured birds resembling Merriam’s, Rio’s and hybrids. We also had birds exhibit behavior of both Merriam’s and Rio’s.

2. We need to look at nesting and fledgling success of birds nesting in the river bottom where Russian olive has been removed.

3. Lastly, we really need to better understand crop damage, real or perceived. Our study really didn’t answer this question for landowners. Future studies to do so would be a positive step toward alleviating perceived and actual conflicts associated with wild turkeys in the southwest.